A meaningless way to make abstraction

Published:

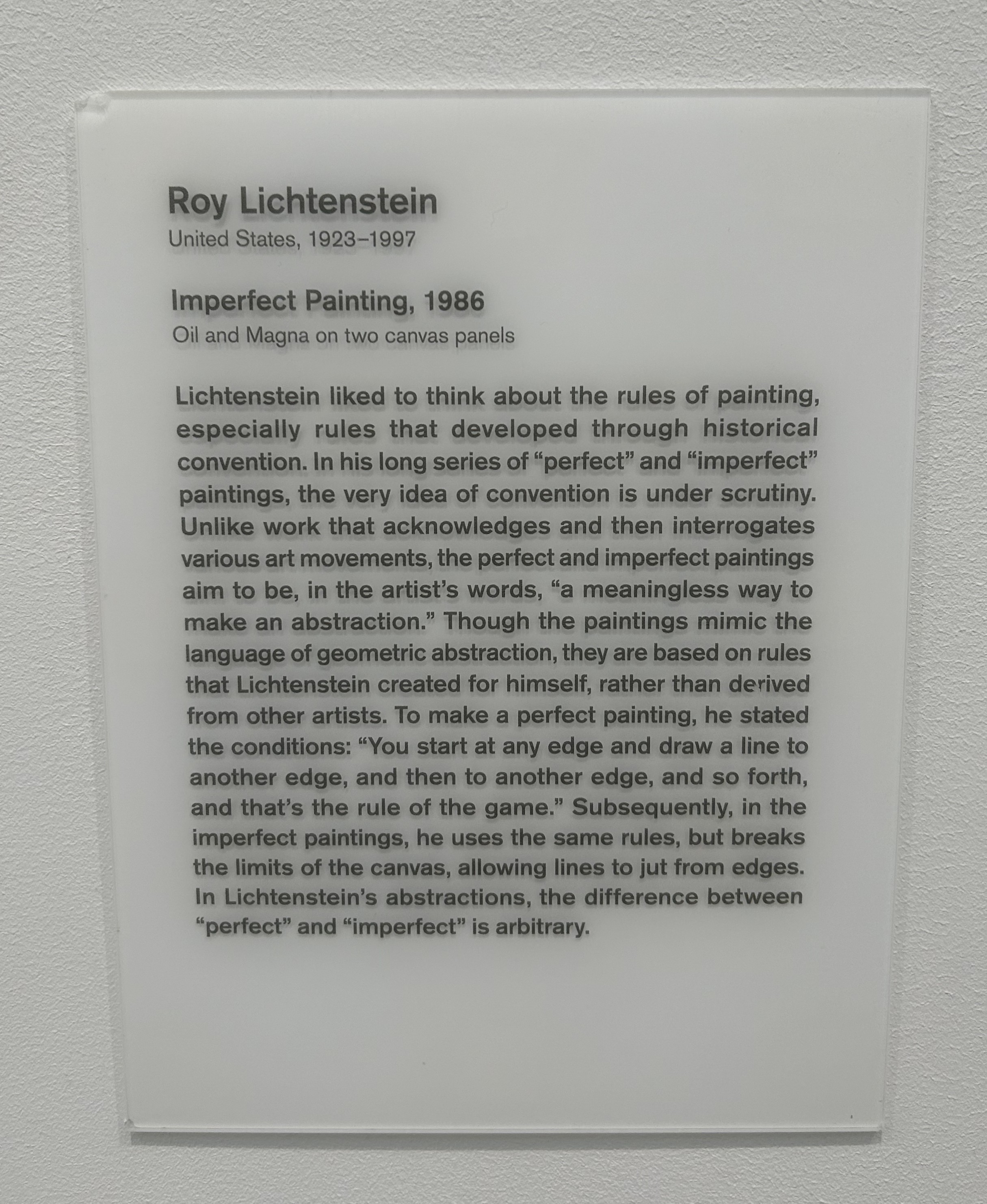

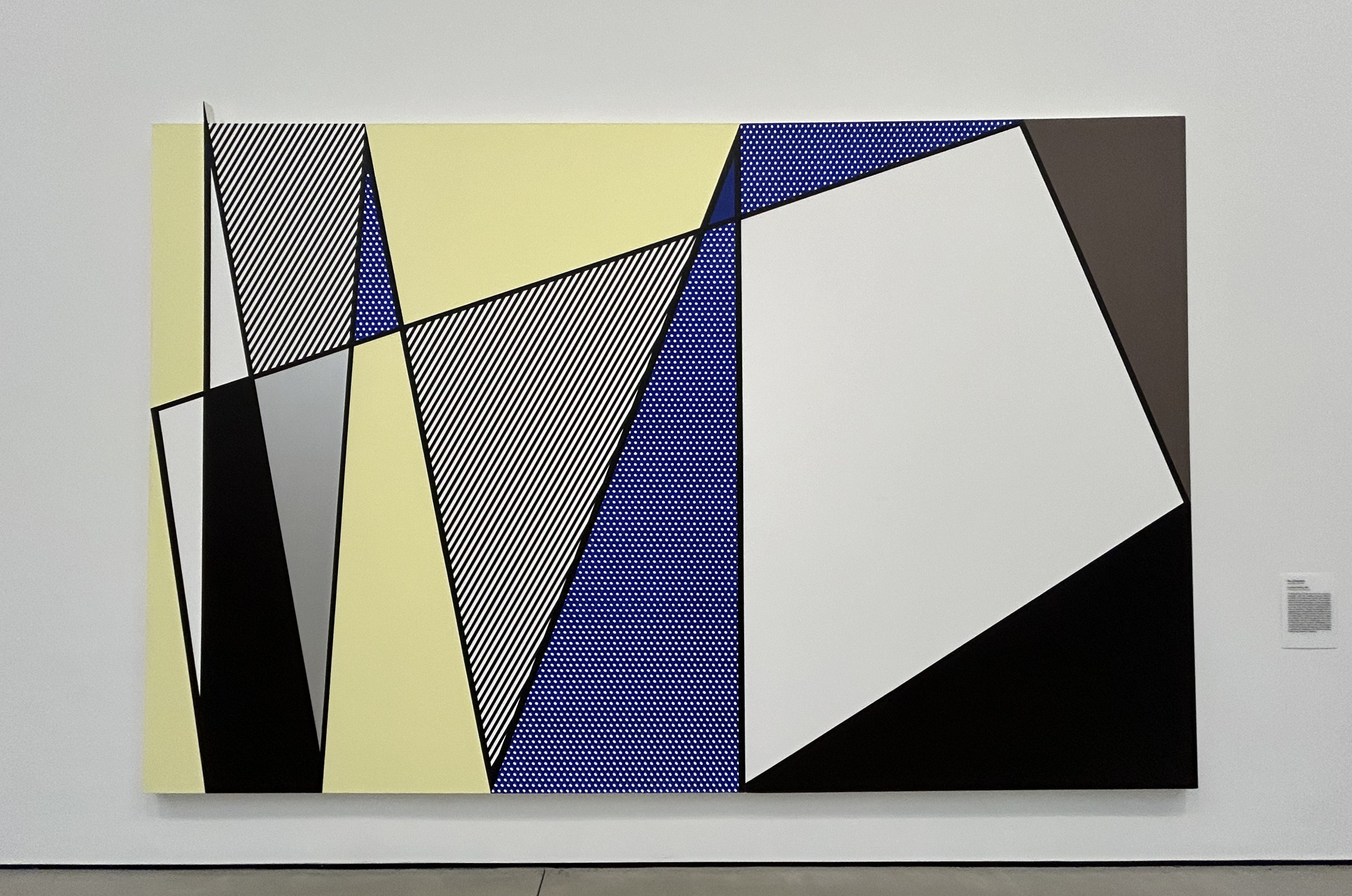

On the treacherous mountain roads of Yosemite, where a single misstep could send a car plunging into the valley below, I found myself unable to concentrate on driving. My mind was utterly consumed by one sentence. Even now, my mind keeps returning to a phrase I saw on the placard next to Roy Lichtenstein’s Imperfect Painting at The Broad museum: “a meaningless way to make abstraction.” The phrase resonated with me so deeply it made my heart race, echoing in my mind. I couldn’t believe that a problem I had been grappling with for the past year could be described so precisely.

You can find a concise and beautiful explanation of the Imperfect series here: 10 Facts About Roy Lichtenstein’s Perfect/Imperfect Paintings. I highly recommend it. But I’m no art critic; what I really want to talk about is how this idea connects to my understanding of psychology and science of science.

Meaningful abstraction

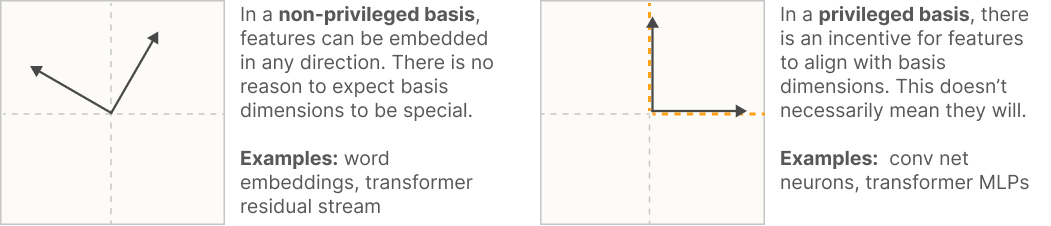

For me, the concept of a “right way to make an abstraction” first clicked when I knew (V)AEs. These are a type of AI model that attempts to find a “true disentangled representation” from data. This idea was further clarified by Anthropic’s work on a “toy model of superposition,”, they show that the neat abstractions we seek are often messy and tangled in LLMs.

Later, in my own work using AI for psychology, we tried to discover new concepts from data, but we always hit the same wall: it was nearly impossible to ensure we had found a “true” or “privileged” axis. This made me wonder: Why was early physics so successful at abstracting “true”—or at least, meaningful—concepts from the world? For example, “force” unites the fall of an apple and the orbit of a planet under a single, elegant equation.

The most remarkable successes of AI4Science have emerged in disciplines with well-defined problem formulations and clear ontologies—such as classical physics, chemistry, and materials science. For example, in classical physics, concepts like velocity, force, and temperature refer to well-defined entities in an objective external reality. Measurements of these physical quantities can be adjudicated objectively, as demonstrated by accurate predictions of planetary orbits or particle trajectories. AlphaFold’s achievement belongs to this category: the three-dimensional structure of a protein is an objective physical fact, providing a natural ground truth that makes its properties straightforward to verify.

Science, and perhaps epistemology itself, is this very process of abstraction: moving from raw observation to a true or useful latent representation, which we call a law or a theory. The concept of “force” discards details like an object’s shape, color, or material, focusing only on the essential property of what changes its state of motion. In parallel, abstract art emphasizes a departure from figurative representation to pursue form, color, and structure for their own sake. By leaving only form behind, this artistic process mirrors science’s method of abstracting forms and laws from nature.

Meaningless abstraction

The success of science, especially classical physics, makes us believe that good abstractions are natural—that they always correspond to a true ontology. We see a neat progression from aether to fields, from spacetime geometry to quantum fields. But when problems become too complex, perhaps even impossible to prove with experiments, are these abstractions still tapping into a true ontology?

In aesthetics, this question is perhaps even more pronounced than in science. What makes an abstraction “true” or “good”? Is it an abstraction of the objective world, or of emotion, of form, of a concept? What kind of abstraction should we choose, or are different abstractions simply different perspectives?

So how do we determine if the abstraction we’ve created is a good one? And what, ultimately, makes an abstraction useful or popular?

In my field, psychology, the greatest challenge lies in its fluid and contested ontology. Psychology grapples with theoretical constructs such as “working memory,” “well-being,” and “subjective value.” These constructs are not directly observable and are often marked by conceptual fragmentation and subjectivity. Psychological constructs are inherently theory-laden abstractions rather than objective entities. Their definitions, boundaries, and even their ontological status are frequently debated within the field. More importantly, our experimental data are theory-dependent: theory precedes data collection, and tasks are explicitly designed to instantiate theoretical assumptions.

For example, consider a foundational question: how do humans make decisions? One prevailing theory assumes that individuals compare a latent variable, called “value,” associated with each option before choosing. This assumption underpins much of the field of value-based decision-making. Framing decision-making as a process of “value integration and comparison” shapes not only theories but also experimental designs. Researchers then use tasks like the multi-armed bandit or other economic games to study how humans integrate value. Consequently, any behavior that doesn’t fit the model of integrating and comparing values is often dismissed as “noise,” an error, or the result of a bad participant.

Another example is “working memory,” defined as a limited-capacity system for maintaining and manipulating information. Consequently, any task designed to measure it must show a capacity limit. If it doesn’t, the task is dismissed as an invalid measure of the construct. The task’s induced performance ceiling is then taken as evidence for working memory, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This dynamic exposes psychological constructs to a form of circular reasoning akin to the “No True Scotsman” fallacy.

These conceptual vulnerabilities become more apparent with the advent of large language models (LLMs), which display cognitive abilities comparable to our own. When we say a human performs “memory” or “reasoning,” we are referring to a narrow set of behaviors, defined and validated by the very tasks created to measure them. But when an LLM also succeeds at these tasks, attributing “memory” or “reasoning” to it feels conceptually strained, especially since we have no idea if its internal processes are anything like ours. This forces us to confront an uncomfortable possibility: that the psychological terms we have long used are not true descriptions of specific internal mechanisms. Instead, they may simply be meaningless abstractions—convenient labels we use to group together a cluster of similar behaviors that arise from a task. These constructs, which we thought were so profound, might be wishful thinking all along: superficial tags that don’t reflect any real, functionally equivalent process.

So, is psychology a meaningless way to make abstractions? The answer depends on what you mean by “meaning,” but meaning itself is a human construct, not a natural law. Could we, then, build another system of constructs—completely different from current psychology—that is still just as meaningful?

Source of abstraction

I’ll admit that modern science is too complex to find a single true ontology (or causal structure, if you prefer). And I’ll concede that psychological phenomena like “working memory” are supported by many experiments designed to test their validity. But let’s step back, where do these concepts come from in the first place?

I think the “good” or “conventional” concepts, the ones that become cornerstones of our thought, are those that capture some recurring “symmetry” or invariance in the world. For example, the concept of “force” works equally well to describe the changing motion of a pushed box or a thrown ball—that is a kind of symmetry. The concept of a “chair” is stable because it satisfies a functional symmetry between the structure of the human body and the action of sitting. Even the apparent asymmetry of cause and effect might derive from the invariance of their representation in a causal diagram.

“Working memory” also attempts to capture such a symmetry; it’s why we have a “magic number” for how many items we can hold in our minds. But this symmetry is fragile. It has a source: the researcher’s perceived pattern. A whole line of experiments is then designed to test against this perceived symmetry. The challenge for psychology is defining what kind of symmetry it is even looking for. Is it a pattern of behavior across situations? A pattern of neural activity across individuals? As it stands, these symmetries appear weak and unstable. Worse, our experiments (like working memory tasks) are designed in a way that artificially manufactures the very symmetry we then claim to “discover,” trapping us in a circular argument. This is why if you change the task from a discrete measurement to a continuous one, the ontology of working memory shifts. The arrival of LLMs forces us to ask if an entirely new, non-human-centric unified system of psychological abstraction is possible. I am not a fan of the reductionist tendencies in psychology, especially the reliance on EEG and fMRI data. I see the rise of LLMs as a golden opportunity for the field—a chance to make our understanding of cognition more abstract, focusing on function and normative principles rather than reducing it to neural patterns.

Humans are good at making abstractions. Whether “true” or not, it generated meaning. We create language and concepts, using them as primitives to communicate and think. All human artifacts can be seen as a form of abstraction, distilled for a specific daily use. Why do we use a chair for sitting and a bed for sleeping, and not some composition of the two? Is it about affordance or function? And why do we define function in this specific way? (Is it just because the human body is shaped the way it is?) Is the concept of a “chair” therefore “true”? To what extent do our concepts align with the world itself? Or do they only align with human perception? Or perhaps, just with the outcomes of human behavior? Anyway, a “meaningless” abstraction acquires meaning simply by being used, discussed, and passed on.

In other words, the source of abstraction is not a true ontology, but our restless ability to create and then break order.

This is why I enjoy science in the same way I enjoy art: for their shared rebellious spirit. Both constantly shatter our default belief that “seeing is believing,” pushing human thought into more complex and abstract realms. By deconstructing old meanings, we can construct new ones. This is the true spirit of science and art.

With his “meaningless” experimentation, Lichtenstein questioned the notion of perfection that permeated ‘high’ art, making a mockery of the art world’s fabricated standards. And just like Lichtenstein, my work on DynamicRL starts as a satire of superstition about symbols (RL) that seem meaningful in psychology, while the work may have ended up genuinely expanding the conceptual boundaries of RL. My collaborator initially found it very strange. He insisted it was no different from a RNN. What he didn’t know was that, at its heart, the project was intended as a mockery. I love it because it breaks a conceptual symmetry.

The effort to make meaningless abstractions is itself meaningful, and perhaps beautiful. It asks: What is the boundary of meaning? Where does meaning come from? How to construct or destroy meaning? And I think those questions should be central to LLM alignment and interpretation, epistemology, and the science of science. “A meaningless way to make abstraction” is not nihilism. It is a necessary scientific and philosophical tool. It is the act of deliberately breaking the “meanings” or “symmetries” we hold sacred in order to explore the true boundaries of our cognition and language. Only then can we clear a path to discovering deeper, more robust truths. This is why I maintain that humans must remain central, even in a future where LLMs surpass us in intelligence.

A final note: Thank you for reading this piece of meaning-less abstraction. I would love to hear any feedback that could make them clearer.

This question has been haunting me on and off for years. At the start of this year, I thought I finally had some answers. With GPT’s help, I even dared to draft a philosophy paper—after one or two months, I discovered my writing made about as much sense as a mumble rap freestyle. Then came a family trip. At the Broad museum, that same artwork poked my brain again, and I decided: fine, I’ll write a blog. Maybe someday it’ll evolve into a real philosophy paper. Or maybe it’ll just sit here forever. Either way, at least my thoughts are out